What I’ve Learned:

“Alu element: The crowd’s not boo-ing, they’re Aluuuuu-ing.”

This is one of those times when being a baseball fan can help you learn something about science.

(All the other times either involve knuckleballs or an obscure branch of physics dedicated to explaining what the hell has kept C.C. Sabathia’s pants up for most of his career. So this one is the best, obviously.)

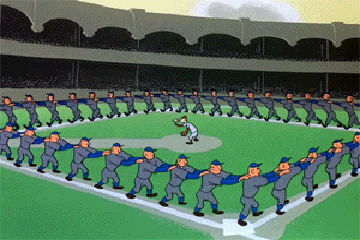

Back in prehistoric times, before most anyone was born probably, people were playing baseball. I’m talking way back, like 1960 or so. It was around that time that major league baseball was invaded by the Alou family. First came Felipe, then his brother Matty — and then his other brother Jesus. And just when you thought there were no more, another Alou family member, Felipe’s kid Moises, joined the league. And Felipe stuck around as a manager, after his playing days were over.

Basically, Alous were everywhere in baseball. You could scarcely swing a dead Louisville Slugger around the majors without thwacking an Alou element. Not that anyone did that, of course. It would be unsportsmanlike.

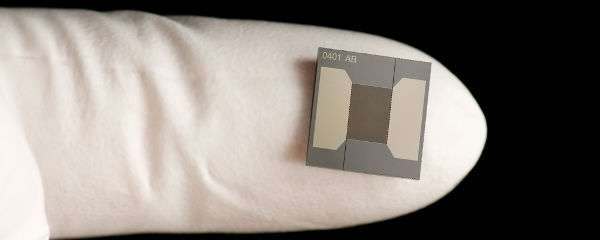

A similar thing happened long ago in our genomes. Tens of millions of years ago, some furry little ancestral critter hiccuped, mutationally speaking, and produced the first Alu element. These Alu elements are short snippets of DNA that got erroneously copied out of a gene, mangled, and jammed back into the genome. The DNA bits couldn’t hit a curveball or shag fly balls, but they did have one major-league talent:

They could make copies of themselves, which could then set up shop in other spots in the genome.

Just like the Alous, who didn’t enter the league at the same time or always play for the same team, the Alu elements gradually spread themselves around. The species in which they first popped up was an ancestor of a set of mammals called Euarchontoglires, or “supraprimates”; these include, among other beasts, rodents, tree shrews and primates — including humans. That means that all these species — again, including humans — have Alu elements hanging out on their genomic rosters. Lots of them.

It’s like the Alous signed on — and then made clones of themselves, until they were everywhere all over the field. Real Bugs Bunny vs. Gas-House Gorillas stuff. Only with less cigar-chomping lunks, and more transposable DNA elements.

In total, Alu elements make up more than ten percent of the human genome, and there are more than a million of them in every person’s DNA right now. A few thousand of those are unique to humans, but most can be found in other animals, like those shrews and monkeys and such mentioned above. That’s how we know Alu elements jumped into the game a long time ago; all of these species still list Alus on the roster.

Most copies of the Alu elements don’t do much, since they’re located in stretches of DNA between genes. By hopping willy-nilly around the genome, Alu elements do increase our genetic diversity — and recent reports suggest they may help defend against toxins and viruses. The many copies can mutate over time, however, and they can insert into some pretty inconvenient places. These buttinski Alu copies have been linked with diseases from hemophilia to Alzheimer’s to type II diabetes to several types of cancer.

Which is where the parallel with baseball breaks down. So far as I know, no Alous ever scrambled anyone’s DNA, or made opposing pitchers more susceptible to developing cancer. Getting sent down to the minors, maybe. But never cancer.

So the Alous and the Alus have a few things in common. They’ve both been around for nearly forever, and there are a zillion of each, all a little bit different. But one is a family of All-Stars and sluggers, while the other is hitching a ride in our DNA like a pack of self-cloning subnuclear stowaways.

No wonder the Alous are the ones on the baseball cards.