What I’ve Learned:

“Properly-punctuated equilibrium: Ten million ellipses, then a whole bunch of exclamation points.”

Punctuated equilibrium sounds like something you get when you perforate an eardrum. Like there should be PSAs about it, with scary pictures of death metal bands and Beats headphones with blood on the cans.

Luckily, it’s not that. No one’s coming to tear the Dethklok from your cold, deaf hands.

Instead, punctuated equilibrium is an evolutionary biology concept that made a big splash in the 1970s. It’s been desplashed a little since then, but it’s still pretty important. Plus Stephen Jay Gould helped think it up, and mostly everybody liked him. So there’s that.

The idea is this: in (at least) some cases, the pressure on organisms to evolve and adapt and squirt out a bunch of funky new species isn’t constant over time. When there’s plenty of food and the water is fine and everybody owns their own TiVo, then it doesn’t matter much if your individual set of genes makes you three percent hardier than your neighbor.

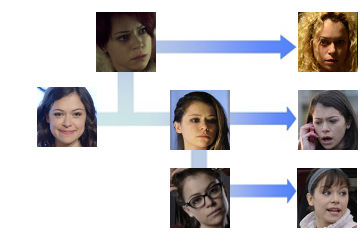

Oh, sure, you might get off your deoxyribonucleic ass and mutate up another leg or some gills or an enzyme to digest styrofoam. But let’s face it: you’ve got a pizza coming, and you’re still catching up on last season’s Orphan Black. Who has the time to speciate? And frankly, why bother?

This could go on for millions, or tens of millions of years.

(Well, Orphan Black won’t, of course. Tatiana Maslany is terrific and all, but she’s going to be too old for this thing at some point. I don’t care how many gills she grows.)

Things get interesting, says punctuated equilibrium, when the going gets tough. If the resources dry up, individuals die out. Small groups get separated from others; exploitable niches become more important. The quickest — and perhaps most radical — to adapt will ultimately thrive. Like the guy who brings a flask to the keg party, in case the beer runs out.

Or something less alcoholic. If you must.

It’s during these periods of ecological pressure and isolation that many new species are born. In between, all the old fern and finch and crocodile species sit around getting fat on Cheetos. And often each other.

But introduce a little hardship, and nature blossoms with adaptation to take advantage. That’s why an oceanful of brine shrimp will remain boring dumb brine shrimp forever. They want for nothing; they’re little trust fund crustaceans, born with silver… um, tiny handled eating utensils that rich baby shrimps would use… in their mouths.

(Or gills. Or whatever. Look, there’s no “aquatic face anatomy” tag on this post, all right? You get the idea.)

However! Scoop a small colony of shrimp out of the sea, stuff them in an envelope and shove them in the mail — now that’s an ecological challenge. And it’s enough to turn them into a whole new species: Sea Monkeys, with legs and fingers and brains and disturbingly human lips and what appear to be testicles growing on stalks out the tops of their heads.

And how does it work? Through the science of punctuated equilibrium.

So far as you know, unless you happen to own any of Stephen Jay Gould’s work. Or a freshman biology book. Or Sea Monkeys.

Stupid Sea Monkeys.