What I’ve Learned:

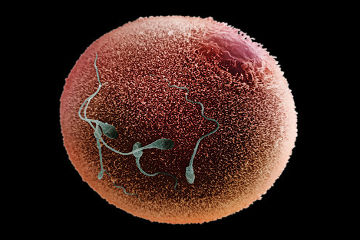

“Scanning electron microscopy – almost as exciting as… well, you know.”

“Scanning electron microscopy” is one of those sciency terms that looks a lot scarier than it actually is. To make sense of it, you just have to break it down, word-by-word. I start at the end and work my way backwards.

(Science is usually more fun that way. Like Harry Potter novels. Or nine-layer dips.)

So, start with “microscopy”. This is just “microscope” with a fancy-sounding “y” glommed on the end. Scientists sometimes add “y” to words to make them sound more impressive — like oncolog or rhinoplast or chemistr, for instance. But don’t be fooled; “microscopy” just means “doing stuff with a microscope”. And “microscope” means “machine that makes tiny things look bigger”.

And if you ask what “tiny things” means, we’re going to talk about your sex life. Don’t be a smartass.

Next is “electron”, which is an especially tiny thing that zips around atoms. Electrons have other properties, of course, like spin and charge and favorite How I Met Your Mother episode, but the important things right now are these: electrons are fast, unbelievably tiny — like, seriously, sextillions of the things in a grain of sand tiny — and can be shot in a tight beam like a skinnier, less murderous laser.

That just leaves “scanning”, which brings everything together. The beam of electrons is shot at the sample inside the microscope.

(Technically speaking, these electrons are said to “bombard” the target. Or in the words of one esteemed science educator:

“Bombardment! Life is pain, son! Bombardment!! My post-doc lasted seventeen years! Bombardment!! Science is a cruel and less-lucrative-than-anticipated mistress! Bombardment! BOMBARDMENT!! BOMBARDMENT!!!”

Yes. “Bombardment”. Thanks.)

Then the beam scans back and forth across the surface, like a printer over a piece of paper. Only instead of shooting ink (or dodgeballs), it’s electrons. These electrons excite the atoms they hit, which sends other electrons pinging off the surface. Scientists detect these “secondary” electron signals to determine the contours of whatever’s being scanned.

Sort of like a hot blind girl feeling your face to figure out what you look like, only with electrons instead of fingers. Also, most microscopic targets are more attractive than Kenneth Parcell. Which is probably good.

This technique is often used to view fixed biological samples (think “teeny critters in formaldehyde”) or the surfaces of materials like crystals or computer chips. But you can see almost anything in a scanning electron microscope, provided you can suck all the water out of it and, if needed, micro-coat it with a conductive material to provide lots of surface electrons.

(For instance, some scientists want to look at spiders. And gold is conductive and easy to layer on. So our universe now contains an actual, once-living gold-plated spider, like a villain in some arachnoid James Bond flick.

Science says, “you’re welcome“.)

By using electrons instead of light, scanning electron microscopes can magnify up to 500,000 times. So you can view bacteria and snowflakes and insect feet and grains of rice in stunning detail, down to a scale of one nanometer.

Which is a little better resolution than the monitor you’re reading this on. Yes, even if it has that “retina thingy”. Trust me.

So don’t get tripped up by the long words and fancy syllables. “Scanning electron microscopy” isn’t something frightening. After all, who’s afraid of a little bombardment?

Bombardment! Bombardment!! BOMBARDMENT!!!