What I’ve Learned:

“Frameshift mutation: be VERY careful with your threesomes.”

Imagine you’re a Subway “sandwich artist”.

(I know, it’s very depressing. I’m sorry. It’ll only take a minute, and I promise you won’t run into that Jared guy. Because, yikes.)

As a sub Salvador Dali — or if you prefer, po’ boy Picasso, grinder Van Gogh or hero Edward Hopper — you follow three steps to create each “munch-sterpiece”:

- Slap down the spongy bread.

- Lay in the meatlike substance.

- Sprinkle various wilted veggies to taste.

That’s the procedure, one two three, into eternity.

(Or until school’s back in for the fall. Or you get fired for having mayo-balloon fights. As one does.)

But what happens when you get the sandwich dance wrong?

A simple screw-up — substituting the bread with cardboard, for instance — would ruin a single sandwich. (Or not. Possibly no one would notice.) Ditto for getting the steps out of order, slapping your meat on your pickles or some such thing.

But what would really throw things into a state of hoagie higgledy-piggledy would be to skip a step (or add an extra), without changing the overall pattern. If you had bread and meat ready, for instance, and momentarily forgot that vegetables existed.

(Hey, this is America. It happens.)

You’d know there’s a third step to the sandwich, so maybe you’d move on to bread and create a bread-meat-bread order. But now you’ve already done the bread step, so even if you remember the veggies — hello, lettuce! — your process is out of sync. Your next sandwich would be meat-veggies-bread, and so would the other subs after it, until you found a way to make an adjustment. Or until the manager fired you, because you’re making sandwiches like a crazy person.

What you’ve just done — apart from the important public service of encouraging people to eat somewhere better than Subway — is called a frameshift. When it happens in a sandwich shop, it gets a little messy. When it happens in your DNA, it’s called a frameshift mutation, and it can be very, very bad.

That’s because of the way that information in DNA gets used to code for proteins, which do most of the important jobs around our cells. Most of the genes in our DNA code for proteins, but the DNA information goes through another form called RNA to make it happen. The RNA gets created directly from the DNA, “word-for-word” as it were. So if a frameshift mutation occurs in the DNA — one missing bit of information, or one extra — it doesn’t make much difference here. The RNA is just a little longer or shorter than it ought to be.

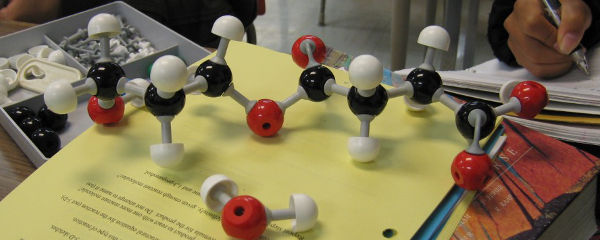

Making RNA into proteins is trickier, though. Here, three bits of RNA information code for individual amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. And just like with the blimpie Botticellis above, if a triad stutters out of frame, everything afterward goes to hell. The wrong protein gets built, shorter or longer and unable to function the way it’s supposed to. It’s basically a Franken-protein, and all because of one little frameshift mutation.

While frameshift mutations are relatively rare, they can have huge consequences thanks to the complete horking-up of proteins they cause. Frameshift mutations can cause conditions ranging from Tay-Sachs disease to Crohn’s disease to cystic fibrosis to cancer, and more. Any of which are significantly worse than not getting lettuce on your footlong Italian.

You can reduce your risk of developing frameshift mutations by staying away from suspected DNA mutagens. Cigarette smoke. Ultraviolet radiation. Possibly, Subway food. So keep those DNA frames in sync and if you forget the veggies, then for heavens sake, start over. Sandwich safety first, kids.